|

Material Sustenance & Family Snapshots

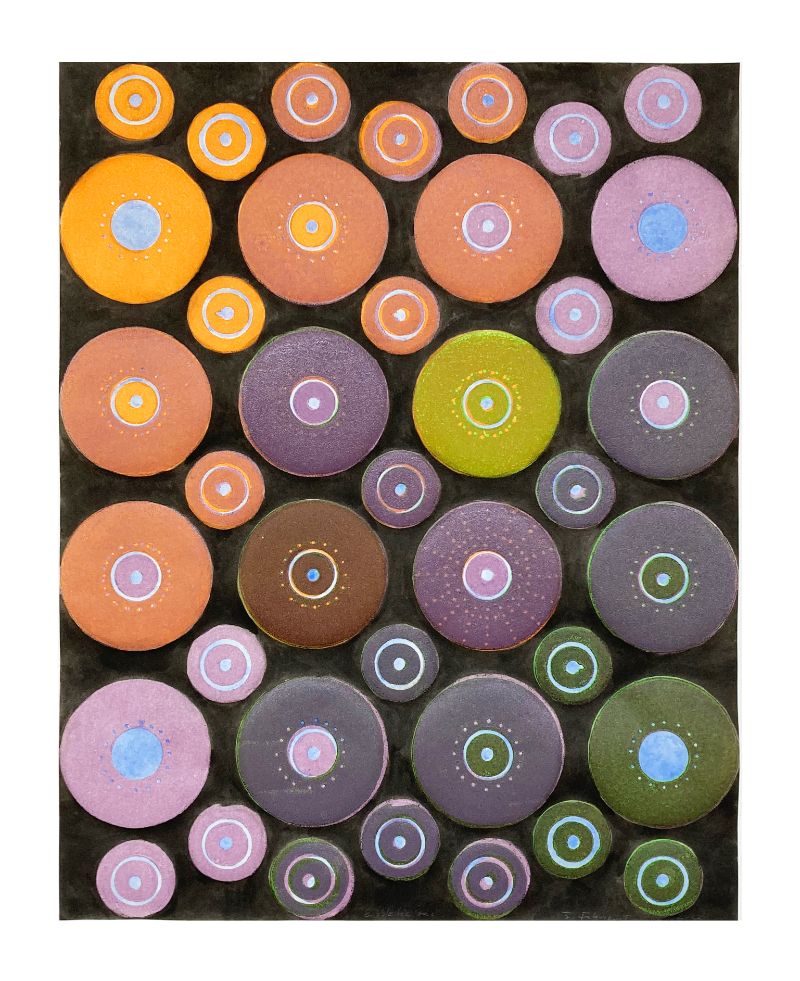

May 27th to July 15th. Opening is May 27th from 4 to 6 followed by a potluck dinner. Material Sustenance includes work by: Frank Jackson Tom Goldenberg Jonathan Fabricant Russell Steinert Family Snapshots is work of Nikko Sedgwick Material Sustenance: Sometimes an art show is not about “the art”. Sometimes it's about the time that the art is made in. This show is a document of how art and life bring meaning to each other. The things that have happened when making the work are often invisible. I invite you to look for the deep relationship between the process of making and the lives of these five artists. The answers they have found are in the relationship of the materials they use to themselves. They are fascinated with the process of creativity. They turn towards an inner world, towards nature, patterns, and to the families each artist has been blessed to live with. Russell Steinert: My approach as an artist is rooted in a sensitivity to place and the histories we carry with us. Developing a relationship to a place in each phase of life involves taking in its textures and noticing the ways oneself stands in relation to it. Encountering a space brings to the surface feelings, memories, and stories from previous places and lives, a fusion of the old and the new. I have been particularly drawn to the intimacy and quiet, yet deeply resonant particularities of the spaces that hold the most meaning: our homes, our places of spirituality, and–for artists–our studios. In my work, I visually tell stories about the connections between these places and the objects within them. I’ve developed a language of painting and building for architectural spaces, images as windows onto the outside, wood fabrication referencing cabinetmaking and toys, hand-sized objects cut from wood to place on and around the cabinetry and on the floor near the paintings I install. My artistic practice plays with the boundaries of what constitutes a work of art, seeking a freshness in the deconstructing of function, frames, and edges to make room for the deeply personal and intimate. Janis Stemmermann: When I first met Russell in 1990, his work was in a transitional period. He had moved to NYC from the Bay area where he had a frothy period of making paintings and exhibiting. In his Brooklyn studio, the objects in his paintings were taking form, he was casting balls in plaster, making objects out of wood. When our children were young, he made them whimsical furniture pieces and objects for their rooms. He started a custom furniture business to make a living, essentially letting go of a studio practice where our family life took over. Years later, after taking our youngest daughter to New York Central for a school project to buy supplies, he came home with tubes of paint for himself. Not asking me to, I cleared out a bedroom for him and his paints in our Brooklyn apartment. For a while he just took naps in there on the floor. The girls and I bought him a small easel for his birthday. We eventually left that apartment and at the same time he began managing an office space on Canal Street in Manhattan. He took a spot in the basement to paint at the end of each day and began creating new bodies of work. As I look back over time, it all adds up: the choices, acts, observations big or small - all evident in the work he is making now.  Steinert, Dresser Painting, 2020, 48” Jonathan Fabricant: My relief print work is a game of chance, a dive into the unknown, an experiment renewed each day. I use the unique qualities of the print process to purposefully distance myself from the immediacy of painting and drawing; a different way of thinking. The print process takes me into the slower more protracted, backwards-puzzle of the multi-layered, printed image; it confounds my expectations and engages me with its own peculiar problems and surprises. I start with a simple unit, printed in different ways. Sometimes I see “things” pop up in the work, usually a visual phenomenon; sometimes an emotional energy, or a trip through time to a “place”; these subjects come to me through the process and are not looked for or intended. The work becomes a presence that introduces itself to me. To be in the studio; to explore the abstract and essential nature of shapes and color; to work with the process of printmaking; These visual elements, are a universal language of their own, not exactly definable, but a profound positive force, that is embedded in everything, both natural and human made; it is a rich world! My practice is a place where I try and quiet the noise, breathe through my anxieties and fears, and move from what is underneath toward what is Visible. Anne Capeci: Being partner to Jonathan has meant a steady hum of tools, music, talk radio, or guitar coming out of his studio while I worked in my home office—sounds that had different peaks and patterns depending on the day but that always sent an energy through the house (his studio took up one floor in the middle of our Brooklyn home) that I missed when for several years I worked in an office in Manhattan. I might not go inside the studio for weeks, and then when I happened to pop in, or when the smells of the night-blooming cereus drew me in, I’d see what Jonathan had been working on. It was ever changing, surprising — explorations into shape, form, and color that evolved within each series and from project to project, always reflecting in some mysterious way Jonathan’s essential self. Our children grew up seeing pieces in progress and finished works that migrated from the studio to the walls of our home. I don’t think they necessarily thought of art-making as a big deal. It was what their dad did the way other dads practiced law or managed the food coop. Yet I know they’ve been shaped by Jonathan’s lifelong journey as an artist. Making art matters. Bringing your true self to your work and your life Matters. A few years ago I was on a zoom call for work, and I was in Jonathan’s studio because the wifi in my office wasn’t working for some reason. A few works in progress were on the wall behind me, and one of my colleagues marveled at them. I remember thinking, “Oh, I guess not everyone gets to live with an artist.”  Fabricant, Bubblelicious XII, 2022, 17 x 22 II Fabricant, Bubblelicious XII, 2022, 17 x 22 II

Tom Goldenberg: These paintings are musings….Poems drawn on the Passage of Time and the Structure of Everyday Life. My compositions are often formed around ancient foundations and inspired by glacial moraine and the rock walls of Northwestern Connecticut. The Ancient Past informs the Present as a poem to our time. Michelle Alfandari: I could write volumes about Tom but the essence of this man is being a painter. While he is a multi-faceted human; the one constant and necessity for him is painting. Making art for Tom is not optional any more than breathing is for the rest of us. He knew it when he was 4 years old and his mother gave him a bucket of water and a paint brush to paint the bricks of their house. He has an acute visual sense. He sees things you and I do not. He takes in a lot of information and with talent, knowledge, and a quest to create an original, engaging and enduring work of art – he does just that. His art breaths as life does because each work is a part of him. He has opened my eyes and enriched my life in a multitude of ways  Goldenberg Pitigliano 72 x 90 Latex on Canvas 2020 Frank Jackson: These paintings are material transformations from the lived to the imagined, and are about tracing a line between then and now, to someplace else. They continue my interest in working with abstraction, and how implications and suggestions of landscape and bodies can cause the paintings to be understood as sites of memory, experience, and potentiality. Within the visual language that I employ, the question for me is how can glimpses of light, moments of fracture, buoyancy, gravity, and material transformation come together to give meaning to these paintings? How can the dualities of site/place, proximity/distance, and time/memory be present, while still allowing room for ambiguity and the creation of a relational arc between the work and the viewer? These questions are held particularly close for me through the poetic materiality of fresco. During the brief passage of time that the intonaco layer of lime accepts pigment and image, surfaces move from wet to dry, color is buried and hardened, and transparency and opacity locate moments of the day. There is an urgency to the material of fresco, and the possibilities and limitations work off each other. These works are a set of ideas and questions. They are meant to poeticize the seen and felt world and to offer another version to consider. .jpg) Jackson CULUS 2020 fresco, egg tempera, graphite, burlap, on board 7” x 8” Family Snapshots, Nikko Sedgwick: The series Family Snapshots is inspired by Edward Steichen's 1955 exhibition, The Family of Man. This allows me to throw a wide net using images of all kinds of people from all different backgrounds and nationalities. These are archetypal images: a mother and child, wedding pictures, a woman pregnant with her first child, etc.... These types of images mark the passage of time and emphasize our mortality, evoking memory and interpersonal relationships. There is a decay/renewal aspect at the core of this work. The first step in my process is a destroying of the image with solvents that cause the emulsion to deteriorate and melt implying not only a painterliness that I strive for, but an animation, energy and manifestation of aura, breath and life that contradicts our conventional notion of a photograph distilling a moment time. Through the process of making this work there is an excavation, a literal peeling away of layers to reveal that which lays beneath that is akin to exhuming something that has been entombed. These layers serve as a metaphor for layers of personality and identity; what we choose to reveal or obscure, our visions of how we perceive ourselves as opposed to how we present, layers of skin, of generations, of self.  Sedgwick Wedding Cake IV Sedgwick Wedding Cake IV |